Fr. Marc Boulos, June 8, 2019

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

To Daniel’s beloved wife, Renae, and his mother, Marcia; To Renae’s mother Claudette and her family; To his sisters, Deborah and Michele; To Giovanni, Alessandro, Isabella, Cezanne and Hudson, and to the least of these, our dearest Hayden: Christ is in our midst!

All of us live with fear. We fear the power that others hold over us; we fear loss; we fear the future; these fears drive us to seek security, almost always, at the expense of the misunderstood other. Sometimes, we are so afraid that we build walls to protect ourselves from them.

The novelty of Daniel del Castillo, a man so valued in his service to the United States, is that his wisdom came from the very people and places we fear. The cultures that animated Daniel’s intellect were the fragments of fallen societies, of once-great civilizations—places where he was able to live and work. This was Daniel’s great fortune since he was under no illusions of permanence.

Scripture itself is an invitation to understand everything from the perspective of the end. This knowledge replaces fear with certainty: that all things are vanity; (Ecclesiastes 1:2) that human power and prestige are passing away; that all men die, and in the end, all nations fail.

For those who accept it, this knowledge instills clarity of purpose, emboldening its adherents to speak and act fearlessly, standing outside of history, in service of the common good.

In the biblical Book of Daniel, we are confronted with the scope of human history, from the Babylonian Empire until the end of days, measured by the rise and fall of empires. Through the twists and turns of humanity’s perpetual instability and cruelty, in the Book of Daniel, it is the Lord’s teaching that remains constant.

It is the Lord’s teaching that brought honor to the prophet Daniel in the midst of Nebuchadnezzar’s court.

It is the Lord’s teaching, handed down to the Three Youths, that set them free from tyranny, giving them the courage to walk about “in the midst of the flames without harm.” (Daniel 3:25)

It is the Lord’s teaching that offers the same freedom to every generation.

From age to age, the God of the Book of Daniel sends his prophet to speak on his behalf in the king’s court; to bear witness to his teaching in the midst of “the lion’s den.” (Daniel 6:16)

We do not know how the Prophet Daniel and the Three Youths ended up in this court; but we do know the path of our beloved Daniel del Castillo.

We know and remember Daniel as an erudite and soft-spoken man, who conveyed a fierce truth with love.

This version of Daniel would not have been possible were it not for the formidable voice of his childhood truth-tellers, a precarious community of refugees and immigrants, who spoke fiercely and lovingly, with no regard for consequence.

Daniel and I were brought up together in what he called our “tight-knit, micro-community,” a small, scrappy immigrant church on St. Paul’s West Side, a poor neighborhood, host to waves of immigrants of many religions and ethnicities; a place where Jewish and Arab immigrants embraced each other genuinely and lovingly. In this setting, the church of our youth, now burned to the ground, was the cornerstone of a once-thriving inner-city Arab-Christian neighborhood.

At the center of this community served our beloved priest and my grandfather, Fr. Essa Kanavati, a Palestinian refugee and a towering father figure in Daniel’s life. A man, who like all those before him, preached fiercely in defense of the love of neighbor against the love of money, which he understood as the Achilles’ heel of his new homeland. He was not wrong.

There were other voices present there, like that of my father, Paul, an Egyptian man whom Daniel once called “a formidable figure [and] a luminary” whose legacy, in Daniel’s words, “still lingers.”

Like the voice of Daniel’s godfather, my Uncle Louie, whose commitment to education played a central and formative role in Daniel’s career as a writer, which began in his twenties, when he himself created educational programs for the Minnesota Humanities Commission.

Daniel and I grew up listening to our dads and my uncles arguing passionately and vociferously about politics, society and religion. These were important confrontations of immeasurable value because they opened our minds to the world of ideas.

“By the very act of arguing,” C.S. Lewis wrote, “you awake the patient’s reason; and once it is awake, who can foresee the result?”

There were other voices still: that of his godmother, my aunt Vickie, and of his beloved mother, Marcia, a daughter of Lebanon, who more than anyone, opened Daniel’s mind to the literature, history, and intellectual life of the Middle East.

As a boy, Daniel used to wait eagerly for his father of Mexican descent, Daniel Sr., to come home from work. Daniel Jr. was always ready to go someplace; to be on the move. Anytime Deb would go for a bike ride, Daniel would hurriedly get ready, grab his bike, and rush to keep up with his big sister. Even as a boy, he seemed to understand that life’s transience demanded action.

They rode their bikes through the old neighborhood, in the seventies and eighties, a place made of the same stuff as Daniel. They must have passed Morgan’s Mexican-Lebanese Deli a thousand times. Just one block from the old church, Morgan’s too, is now gone.

Bike-riding was replaced with intellectual exchange, as Daniel tagged along with Deb to the Walker Art Center, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the ballet, the Guthrie Theater, and countless academic meetings on social issues, the Middle East, politics, and race.

Daniel was a curious child surrounded by books. Like so many thinkers who came of age in the seventies and eighties, he felt a deep sense of alienation from the culture, a sentiment amplified by the color of his skin. This alienation drew him closer to societies and ideas often dismissed, if not despised, by the American mainstream. Societies where the truth—that all men die and all nations fail—need not be explained.

His parents’ library contained ethnographies, liturgical texts, great works in sociology, books of poetry and theology, and a diverse collection of literary works favoring no single culture.

Bertrand Russel, Khalil Gibran, Erich Fromm, Franz Kafka, Edward Said, and other giants contributed to an early intellectual life that pointed outward and eastward. Art was also an important component of Daniel’s formation. It began with the Levantine iconography of our childhood church, but came into focus with Marcia’s emphasis on aesthetics.

Always a writer, a precocious Daniel used to recount the evening news for his mother and sisters, retelling stories from different perspectives. He was captivated by the power of sharing information in order to educate. Later, as a photographer and writer, he brought the perspective of the outcast and the misunderstood other to the center of his work.

At university, Daniel mastered the Arabic language, discovering the music of Um Kalthoum and the poems of Kabbani, Al Muttanabbi, and Mahmoud Darwish, which he could recite by memory:

“Words sprout like grass from the prophetic mouth of Isaiah: ‘If you won’t believe now, you’ll never believe.’ I walk as if I were someone else. My wound is a white rose of the gospels. My hands are two pigeons hovering around a cross carrying the weight of the earth.” – Mahmoud Darwish

These verses, of exile and suffering, heightened Daniel’s moral sensibilities and focused his life-long priorities. When he, Deb, Giovanni, and Alessandro traveled through southern Lebanon, Daniel photographed the bullet-ridden towns and places of massacre. He trusted the conscience of his audience—anyone willing to look—to see the truth of the misunderstood other in his photos.

This pattern in Daniel’s work, of seeking out the unheard, drew strength from his childhood truth-tellers, who spoke clearly and fearlessly.

At the Minnesota Humanities Commission, for the first time, Daniel’s alienation was transformed into purpose, when he stood up for a friend whose skin color and accent drew mistreatment. Faced with an uncomfortable racism often disguised as “Minnesota nice,” he challenged colleagues to broaden their perspectives in the same way the refugee and immigrant truth-tellers in his life challenged each other.

Daniel secretly sent a letter to the Commission, type-written on letterhead of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, inviting the Commission to collaborate with Palestinian institutions.

They were terrified, but Daniel was satisfied. The letter had exposed a truth, that racism is fueled by our fear of what might happen to us and of what might be lost if we open ourselves to the misunderstood other.

It is fear that builds walls and alienates us from each other, it is fear that tears down bridges.

It must have been hard for Daniel to admit that it was a prank. Still, the letterhead was authentic, one of many treasures gathered from his travels.

When the king sought the death of Babylon’s would-be soothsayers, it was Daniel, the mighty prophet, who took courage from the Lord’s wisdom to confront the captain of the king’s guard:

“Do not destroy the wise men of Babylon,” he exclaimed, “Take me into the king’s presence, and I will declare the interpretation to the king!” (Daniel 2:24)

In similar fashion, our Daniel always spoke up in those moments that mattered most, never cowering from an opportunity to speak the truth, no matter the risk. From his early years in Egypt and Lebanon to more recent endeavors in Afghanistan and Iraq, Daniel was fearless in seeking the truth and speaking it with disciplined clarity.

In the book of Daniel, when the king threatened to murder the Three Youths for refusing to worship his gods, they were fearless—even defiant—in their response. They explained to the king, that it was their God, not the king, who had the power to save or destroy them, and they were willing to take this stand, even if God himself chose not to intervene on their behalf. (Daniel 3:18)

It is the end that clarifies. It is the end that creates wisdom, granting youth the experience of age. It is knowledge of the end that quiets our fears, giving us courage to stand in the face of tyranny.

These men did not fear the king, because they knew that everything comes to an end, including themselves, including the king, including Babylon. Their fealty was not to a man, but to a teaching. They knew that what endures is the wisdom of God that safeguards life in the midst of the flames of tyranny, from age to age. Knowing this end gave our Daniel courage, direction, and purpose in these worrisome times. His death affords each of us the same opportunity.

In Afghanistan, Daniel’s journalism came at the risk of his own life. He entered the country on September 10, 2001 in pursuit of a story on education under the Taliban. He was able to interview two Afghan scholars at Kabul University before his trip was cut short by the fateful events of September 11. At once, his life was in danger.

Daniel did not have permission to leave the country, and the Taliban were in no mood to accommodate. Were it not for his minder, who risked his life to warn him, Daniel may have been imprisoned, or worse. This brave man helped disguise Daniel as a member of the Taliban and daringly smuggled him out of the country. As an advocate for the marginalized, it bothered Daniel that his work put someone else in danger. In later years, Daniel expressed regret at not knowing the outcome of his friend’s life. He could never live comfortably knowing how this man and countless others in the Middle East lived so precariously.

During his years in Lebanon, Daniel wrote for The Daily Star, the famous English language newspaper headquartered in Beirut.

His articles told stories to educate and build bridges in Lebanon’s post civil war era. Daniel understood the pain of alienation that came from his own life. Instead of wallowing, he sought to heal the wounds of isolation afflicting the misunderstood other.

He conducted personal interviews with pivotal figures of the Middle East, among them, Hasan Nasrallah, Walid Jumblatt, and Hanan Ashrawi.

He wrote about politics and religion, in Lebanon, topics that are inseparable. Daniel was a Greek Orthodox who sojourned in the minority Druze community. He spent time in their villages and sacred spaces. He embraced the Druze people with a spirit of humility and a genuine desire to understand. Perhaps that’s why Jumblatt was so open to speaking with him—our Daniel—the marginalized boy who served at the altar with Fr. Kanavati in his precarious but scrappy micro-community.

“Love,” Dr. King wrote, “is not this sentimental something that we talk about. It’s not merely an emotional something. Love is creative, understanding goodwill for all men.”

“It is love that will save our world and our civilization, love, even [and especially] for [our] enemies.”

Our Daniel, the builder of bridges, sought human connection for all of us—across all manmade boundaries. Our Daniel, a man who would be summoned to advise generals and presidents.

Daniel’s first exposure to government service was in Iraq, where he interpreted—not dreams—but the Iraqi press for the local ambassador. Later, as a Foreign Service Officer, he would travel the world. More than once during his career, Daniel was requested “by-name,” for dangerous assignments, to fill difficult and sensitive diplomatic posts, a rare and significant honor in the US Military.

During his tour of duty in Nepal, an American boy went missing. In despair, the young man’s parents reached out to former Vice President Walter Mondale with a simple request, “Please, help us.” Mr. Mondale called Daniel.

It was difficult, but with a perseverance he learned from my grandfather, Daniel found their son. The boy had died while hiking alone in the mountains. Daniel wrote a heartfelt letter, comforting the parents in the face of immeasurable sorrow.

“What I remember best about Daniel,” a colleague wrote, was his ability “to reach out to the parents and families of American citizens involved in…our most tragic cases and…to say just the right thing to let them know he felt their loss deeply and would do all that he could to help. He made many people feel just a little bit better at what must have been the worst [hour] of their [life].”

“Even in the inevitable moments,” King wrote, “when all seems hopeless, men know that without hope they cannot really live, and in agonizing desperation they cry for the Bread of Hope.”

The Bread of Life: the teaching of a Crucified King, who instead of consuming his subjects (Micah 3:3) is consumed by them. (1 Corinthians 11:24)

Daniel was in Stuttgart, Germany, when he was ordered to report to the White House under the administration of President Barak Obama, to be the Director of East African Affairs on the staff of the National Security Council. Later, he was assigned to the office of the Secretary of State. The details of Daniel’s service during these years are unknown to us. One thing we do know, Daniel had a parking space at the White House.

As Daniel’s colleague in the Foreign Service, Dan Hamilton, explained, “The stories about this guy go on, and on, and on, and on.”

“Daniel,” he confided, “always, always remembered his family and the community from where he came, and remembered that everything he did…he did in their names and on their behalf. We will always, always remember him and the principles he embodied.”

“The community from where he came”—made up of refugees and immigrants from places often dismissed, if not feared, by the American mainstream—a church community judged by God, burned to the ground and long gone. A reminder of what Daniel knew to be true: that all things are vanity; all things are passing away, and all men die. It is this truth that gave him courage, direction, and purpose in these worrisome times. Daniel, too, is now gone. All that remains is the teaching he received; the teaching that sustained him; the hope for the next generation.

For as long as I can remember, Daniel was the one person in the room you could count on to say the thing that needed to be said, no matter how uncomfortable the situation. In this sense, he reminded me of my dad. No conjecture, just analysis based on facts and the courage to speak it, no matter the rank of dissenting voices. That is exactly how he conducted himself as a Foreign Service Officer. His fealty, Mr. Hamilton explained, was not to a man, but to his oath, to uphold the law of the land.

Daniel knew that evil—the product of human fear—was real. This knowledge amplified the biblical and prophetic voice always at work on his conscience—in the face of unthinkable moral dilemmas—always prodding him and renewing his mind in the service of “that which is good and acceptable and perfect” in the sight of the Lord. (Romans 12:2)

In this sense, Daniel was a double agent: a citizen of the coming Kingdom who found himself working inside the government of the present one. (Galatians 1:4)

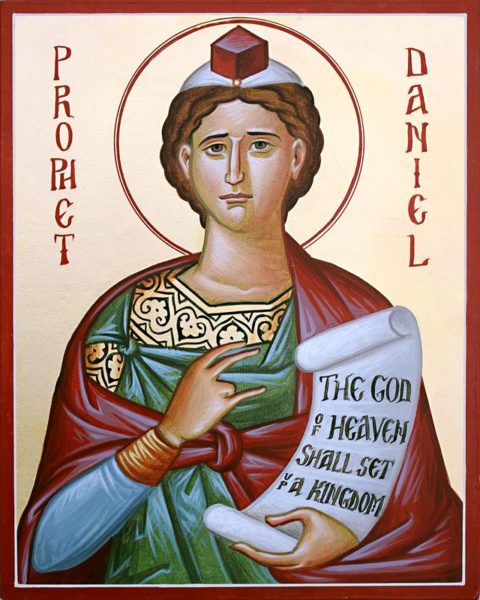

“The God of heaven,” proclaimed Daniel to the king, “will set up a Kingdom which will never be destroyed, and that kingdom will not be left for another people; it will crush and put an end to all these kingdoms, but it will itself endure forever.” (Daniel 2:44)

Deb recalls the day that Daniel left for Egypt to study at the American University in Cairo. He kneeled down and put his arms around his family—around Giovanni, Alessandro, and a one-year-old Isabella cradled in Michele’s arms—then bowed his head low and wept.

Until the very end, he quietly kept tabs on all his nieces and nephews, following the lives of Giovanni, Alessandro, Isabella and Cezanne, forever consulting with his mother and sisters about their wellbeing and hopes for the future. Over the years, Michele kept the hearth warm for Daniel. When duty allowed, he would stop by her house to embrace the kids, forever renewing the tears of his regret for the pain of time lost.

In the many and various ways in which each of us are called, those who serve the common good pay a high price, as do their families.

Daniel found comfort in Michele’s concern for his family during his travels, especially in later years, when the demands of his job left little opportunity for connection with loved ones. Michele’s hospitality towards his wife, Renae, and her family, became ever more crucial as his health failed.

Daniel loved Renae. Their marriage of twenty-three years was the fulfillment of his testimony to his mother and sisters: that Renae was his soul mate and the love of his life, the place his heart found intimate kinship. Their commitment to each other, and Daniel’s love for her mother Claudette and her whole family, are a memory of immeasurable value to be cherished and lived.

Dearest Renae, we give thanks for the life you shared with Daniel. No words can fill the emptiness of your sorrow, save the Lord’s wisdom, which opens our eyes to the beauty that Daniel saw in others—the beauty he saw in you. Daniel was moved by the Scripture readings that you and your siblings shared at your father’s funeral. I pray that we have done the same for your husband. Your love, the gift of so fortunate a marriage, made Daniel’s life possible. May his memory and the bond of love that drew you together be eternal.

Daniel was born with a heart murmur. Marcia and Daniel Sr. spent many sleepless nights knowing that their little boy might not make it to adulthood.

Dearest Marcia, none of us understand the pain of your loss. As an elder mother, you are a sacred presence in our community, a biblical sign of the merciful womb that bore us in the church of our youth. None of us can comfort you in your loss, nor will I speak the empty words of vain men, that “no mother should see her son die.”

I will not speak it and you will not allow it, for how many mothers have lost their sons to violence or poverty?

No. For you, it is the will of God that fills your sorrow with the hope of his teaching for the next generation. The teaching you whispered into Daniel’s ear as you nursed him. Even now, this wisdom nourishes countless people you’ve never met. Now, it is Daniel’s legacy that lingers. May the knowledge of this truth fill your days with meaning.

What I remember most is the Daniel of my youth. The brother who served with me at the Lord’s altar. The Daniel who once gave me his liturgical robe to save me from embarrassment; the boy who always rushed to encourage others. The young man who walked to church early every week to assist my grandfather.

I see the same values at work in Daniel’s nephew, Hayden, who, like his uncle, stands by me at the altar. In a twist of fate stranger than fiction, in the very same neighborhood.

To you, Hayden, I now speak the words of Maya Angelou on your uncle’s lips, a call to arms from beyond the grave:

“Nothing will work unless you do.”

Just as you did on this most important day, your uncle stood before the sacred step at St. Elizabeth and proclaimed to all the Epistle of St. Paul, in letters divinely inscribed:

“For the word of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. For it is written, ‘I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever I will thwart.’” (1 Corinthians 1:18)

Daniel and I were two kids from a scrappy little church long since gone, like the towns and villages its founders left behind. Two kids from the West Side, from an immigrant and minority community, mostly invisible and seemingly unimportant, in an era when religion and our Arab roots remain the butt of the joke. But we both shared something powerful in common:

We were not ashamed.

In time, our pride, the meaning of those days, and its moral imperative would shape our respective paths:

“For consider your call, brethren; not many of you were wise according to worldly standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth; but God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong, God chose what is low and despised in the world, even the things that are not, to bring to nothing the things that are, so that no human being might boast in the presence of God.” (1 Corinthians 1:26-29)

“Let him who boasts, boast in the Lord.” (1 Corinthians 26:31)

Daniel, in Hebrew, means “God is my judge,” a name handed down to him from his paternal grandmother, Refujia, whose name, in Spanish, means “refuge.” We commit our brother Daniel to the merciful Lord, our compassionate judge, who is present to us in the death of human might and prestige.

May this God, our heavenly Father, grant our brother Daniel rest in the bosom of Abraham, together with our Lord Jesus Christ and all the saints, who from age to age have been our refuge and help; through the grace and compassion of his all-holy, good, and life-creating Spirit; now and always, in the hope of his Everlasting Kingdom. Amen.